here you can write some thing...

Git's design is a synthesis of Torvalds's experience with Linux in maintaining a large distributed development project, along with his intimate knowledge of file-system performance gained from the same project and the urgent need to produce a working system in short order. These influences led to the following implementation choices:

Git supports rapid branching and merging, and includes specific tools for visualizing and navigating a non-linear development history. In Git, a core assumption is that a change will be merged more often than it is written, as it is passed around to various reviewers. In Git, branches are very lightweight: a branch is only a reference to one commit. With its parental commits, the full branch structure can be constructed.

Like Darcs, BitKeeper, Mercurial, Bazaar, and Monotone, Git gives each developer a local copy of the full development history, and changes are copied from one such repository to another. These changes are imported as added development branches and can be merged in the same way as a locally developed branch.

Repositories can be published via Hypertext Transfer Protocol (HTTP), File Transfer Protocol (FTP), or a Git protocol over either a plain socket, or Secure Shell (ssh). Git also has a CVS server emulation, which enables the use of existent CVS clients and IDE plugins to access Git repositories. Subversion repositories can be used directly with git-svn.

Torvalds has described Git as being very fast and scalable, and performance tests done by Mozilla showed that it was an order of magnitude faster than some version-control systems; fetching version history from a locally stored repository can be one hundred times faster than fetching it from the remote server.

The Git history is stored in such a way that the ID of a particular version (a commit in Git terms) depends upon the complete development history leading up to that commit. Once it is published, it is not possible to change the old versions without it being noticed. The structure is similar to a Merkle tree, but with added data at the nodes and leaves.[40] (Mercurial and Monotone also have this property.)

Git was designed as a set of programs written in C and several shell scripts that provide wrappers around those programs. Although most of those scripts have since been rewritten in C for speed and portability, the design remains, and it is easy to chain the components together.

As part of its toolkit design, Git has a well-defined model of an incomplete merge, and it has multiple algorithms for completing it, culminating in telling the user that it is unable to complete the merge automatically and that manual editing is needed.

Aborting operations or backing out changes will leave useless dangling objects in the database. These are generally a small fraction of the continuously growing history of wanted objects. Git will automatically perform garbage collection when enough loose objects have been created in the repository. Garbage collection can be called explicitly using git gc --prune.

Git stores each newly created object as a separate file. Although individually compressed, this takes a great deal of space and is inefficient. This is solved by the use of packs that store a large number of objects delta-compressed among themselves in one file (or network byte stream) called a packfile. Packs are compressed using the heuristic that files with the same name are probably similar, without depending on this for correctness. A corresponding index file is created for each packfile, telling the offset of each object in the packfile.

Newly created objects (with newly added history) are still stored as single objects, and periodic repacking is needed to maintain space efficiency. The process of packing the repository can be very computationally costly. By allowing objects to exist in the repository in a loose but quickly generated format, Git allows the costly pack operation to be deferred until later, when time matters less, e.g., the end of a work day. Git does periodic repacking automatically, but manual repacking is also possible with the git gc command. For data integrity, both the packfile and its index have an SHA-1 checksum inside, and the file name of the packfile also contains an SHA-1 checksum. To check the integrity of a repository, run the git fsck command.

Another property of Git is that it snapshots directory trees of files. The earliest systems for tracking versions of source code, Source Code Control System (SCCS) and Revision Control System (RCS), worked on individual files and emphasized the space savings to be gained from interleaved deltas (SCCS) or delta encoding (RCS) the (mostly similar) versions. Later revision-control systems maintained this notion of a file having an identity across multiple revisions of a project. However, Torvalds rejected this concept. Consequently, Git does not explicitly record file revision relationships at any level below the source-code tree.

These implicit revision relationships have some significant consequences:

It is slightly more costly to examine the change history of one file than the whole project. To obtain a history of changes affecting a given file, Git must walk the global history and then determine whether each change modified that file. This method of examining history does, however, let Git produce with equal efficiency a single history showing the changes to an arbitrary set of files. For example, a subdirectory of the source tree plus an associated global header file is a very common case.

Renames are handled implicitly rather than explicitly. A common complaint with CVS is that it uses the name of a file to identify its revision history, so moving or renaming a file is not possible without either interrupting its history or renaming the history and thereby making the history inaccurate. Most post-CVS revision-control systems solve this by giving a file a unique long-lived name (analogous to an inode number) that survives renaming. Git does not record such an identifier, and this is claimed as an advantage. Source code files are sometimes split or merged, or simply renamed, and recording this as a simple rename would freeze an inaccurate description of what happened in the (immutable) history. Git addresses the issue by detecting renames while browsing the history of snapshots rather than recording it when making the snapshot. (Briefly, given a file in revision N, a file of the same name in revision N--1 is its default ancestor. However, when there is no like-named file in revision N--1, Git searches for a file that existed only in revision N--1 and is very similar to the new file.) However, it does require more CPU-intensive work every time the history is reviewed, and several options to adjust the heuristics are available. This mechanism does not always work; sometimes a file that is renamed with changes in the same commit is read as a deletion of the old file and the creation of a new file. Developers can work around this limitation by committing the rename and the changes separately.

Git implements several merging strategies; a non-default strategy can be selected at merge time: resolve: the traditional three-way merge algorithm.

--Linus Torvalds

octopus: This is the default when merging more than two heads.

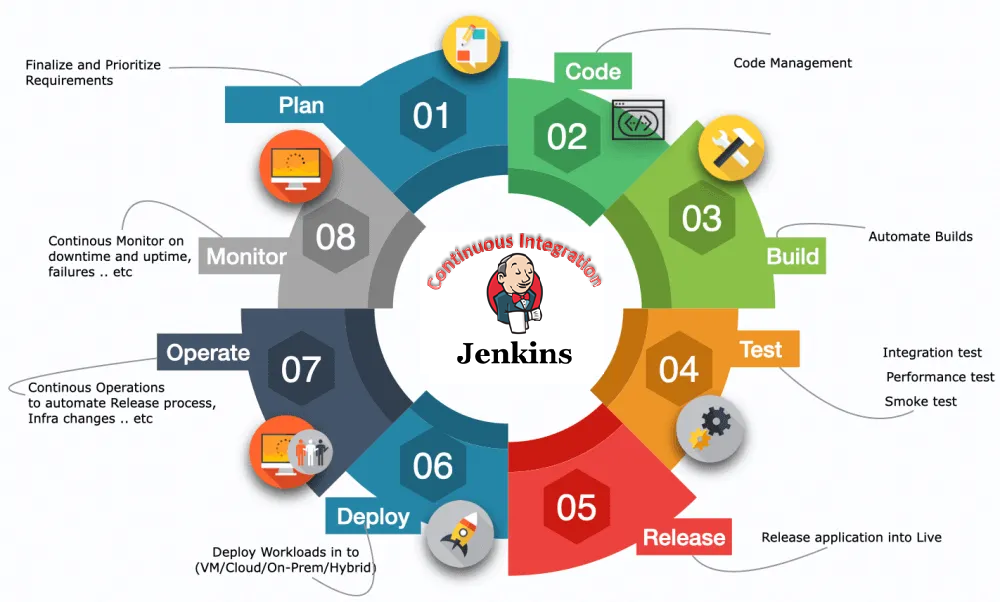

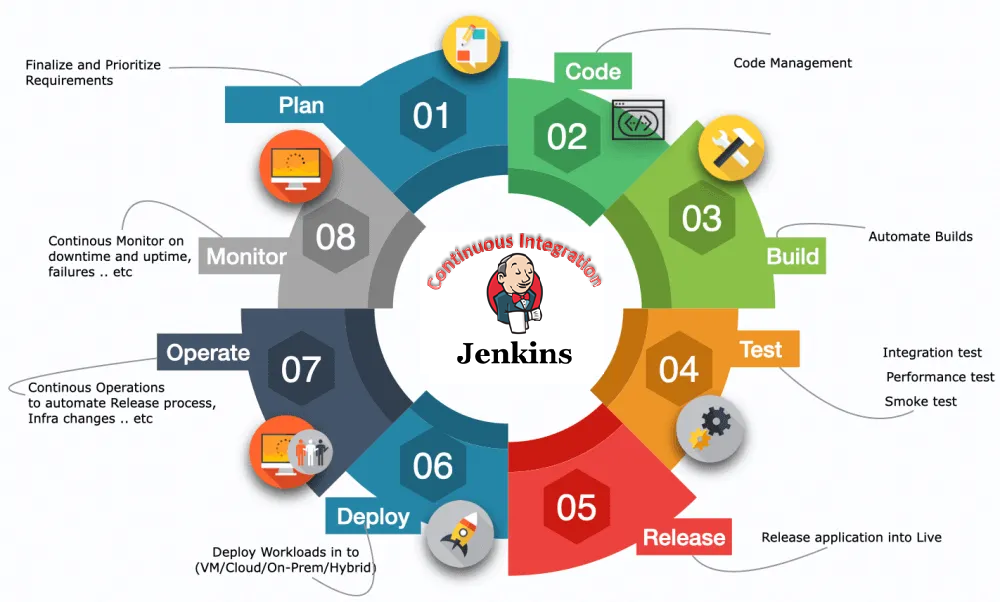

The DevOps seminar will help you to learn DevOps from scracth to deep knowledge of various DevOps tools such as fallowing List.

Kubernetes.

here you can write some thing...

here you can write some thing...

here you can write some thing...

here you can write some thing...

here you can write some thing...

here you can write some thing...

here you can write some thing...

here you can write some thing...

here you can write some thing...

here you can write some thing...

here you can write some thing...

here you can write some thing...

here you can write some thing...

here you can write some thing...

here you can write some thing...

here you can write some thing...

here you can write some thing...

here you can write some thing...

here you can write some thing...

here you can write some thing...

here you can write some thing...

here you can write some thing...

here you can write some thing...

here you can write some thing...

here you can write some thing...

here you can write some thing...

here you can write some thing...

here you can write some thing...

here you can write some thing...

here you can write some thing...

here you can write some thing...

here you can write some thing...

here you can write some thing...

here you can write some thing...

here you can write some thing...

here you can write some thing...

here you can write some thing...

here you can write some thing...

here you can write some thing...